- Home

- Cathleen Young

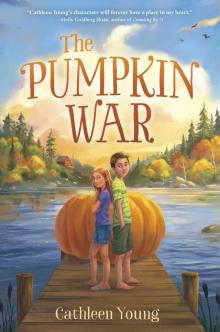

The Pumpkin War

The Pumpkin War Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2019 by Cathleen Young

Cover art copyright © 2019 by Jen Bricking

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Wendy Lamb Books and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Young, Cathleen, author.

Title: The pumpkin war / Cathleen Young.

Description: First edition. | New York : Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, [2019] | Summary: Twelve-year-old Billie enjoys summer on Wisconsin’s Madeline Island, where she harvests honey, mucks llamas stalls, and grows a giant pumpkin, determined to reclaim her title in the annual pumpkin race. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018005490 (print) | LCCN 2018013438 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-5247-6735-8 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-5247-6733-4 (trade) | ISBN 978-1-5247-6734-1 (lib. bdg.)

Subjects: | CYAC: Farm life—Wisconsin—Fiction. | Family life—Wisconsin—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Pumpkins—Fiction. | Racing—Fiction. | Islands—Fiction. | Wisconsin—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.Y743 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.Y743 Pum 2019 (print) | DDC [Fic]—dc23

Ebook ISBN 9781524767358

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

June

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

July

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

August

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

September

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

7 x 1027

That’s a number. It means seven billion billion billion. It’s the number of atoms in a human body. If you wrote it out, it would be a 7 followed by 27 zeroes.

I dedicate this book to 3 people: 2 precious daughters, Shaelee Sean DeCarolis and Gemma JoLee DeCarolis, and 1 wonderful husband, Patrick DeCarolis.

When I see all of you, when I talk to any of you, when I think of each of you, every atom in my body spins extra fast with happiness and gratitude and disbelief at the miracle of my family. Because of you, my universe is filled with love and laughter and happiness.

Every. Single. Day.

I watched Sam through my binoculars as he planted his pumpkin seedlings. He looked like a two-legged bug I could squash with my thumb.

I climbed higher through a web of tangled branches and emerald-green leaves smeared with sunlight, my binoculars swinging from a braided lanyard around my neck.

My head popped into open sky.

I could see my whole world from up here. Our house looked like a wooden bird that had crashed into the hillside. My dad built it with his own hands before I was born. He says our house is “in harmony with nature.” I say it’s weird to have a closet hacked from brownstone and a tiny trickle of a stream cutting through the middle of our kitchen during the rainy season.

Up the hill from my house, at the end of a skinny dirt footpath, I spotted my beehives, a row of white wooden boxes stacked like suitcases.

I love my bees. They turn the world into a taste.

When I stick my finger into a fresh comb bursting with honey, I can taste the globe mallows that tickle my neck when my little sister and I lie sprawled on our backs behind the barn, eating sticky jelly beans from my secret stash, and I can smell the purple lupine that explodes across the fields around my house after a spring thunderstorm. I swear I can even feel the cool breeze hitting the brittlebush in the heat of summer.

Sam says that’s impossible, that it’s just my overactive imagination at work.

What does he know.

I could see my half-built tree house stuck in a towering pine tree and our gray barn slouched next to the feed shed. Our water tank looked like a fat red Tootsie Roll stuck in the middle of the meadow that rolls down from our farm to Chequamegon Bay.

Pronounced she-wah-me-gan.

The bay used to be called Zhaagawaamikong. It was named by the Ojibwe, who lived here first until we stole their land. I guess I shouldn’t say we, since I’m half Ojibwe from my mom’s side. My dad is Irish. When I look in the mirror, I see his red hair and green eyes.

The wind kicked up, and whitecaps skittered across the bay. I raised my binoculars and scanned the horizon until I spotted my dad’s fishing boat, her bow riding low with his haul of whitefish. He named his boat Niinimooshe for my mom, to honor her heritage. Niinimooshe means “sweetheart” in Ojibwe.

My mom thinks that’s romantic. If she spent as much time on that stinky boat as I did, she might not think so.

I swung my binoculars back toward land and found Sam, still planting his seedlings. All of a sudden he looked up and smiled in my direction. I ducked into the leaves as a prickly heat crawled up my neck and across my face.

Sam used to be my best friend, and he’d like to be my best friend again, but that’s never going to happen after what he did last summer.

* * *

That night, we had tofu for dinner. Even if you try to drown it in sesame sauce, it still tastes like tofu.

We used to eat meat. Teriyaki steak. Swedish meatballs. Polish sausage. Those were the good old days.

Marylee ruined everything a year ago when she turned five. That’s when my little sister put two and two together and realized the steak on her plate used to be alive.

Now she won’t touch meat. She won’t even look at it. And there’s no talking her into it. Believe me, we’ve all tried. It turns into a lot of yelling (my dad) and crying (my sister) and pleading (my mom) and more yelling (me), and by then no one wants to eat anything anyway.

So we eat a lot of tofu. Mom calls it a “perfect protein,” but if you go by taste, it’s far from perfect.

“The baby kept me up all night,” Mom said, shoveling chunks of buttery baked potato into her mouth.

“How?” Marylee asked. “He’s not even born yet.”

“He likes to kick.”

My mom was so big, she had to sit a mile back from the kitchen table and rest her plate on her belly.

“Can’t you make him stop?” Marylee asked.

“Baby’s the boss,” Mom sighed. “In a few more weeks, your new brother will be right here with us.”

While Mom stuffed a piece of not-so-perfect protein into her mouth, my sister dropped her broccoli on the floor and

squished it through the heating vent under her chair. She might be a vegetarian, but even she has her limits.

“Good news, Billie,” my dad said, his elbows resting on the edge of the kitchen table, which was a slab of granite that grew out of the floor like a giant mushroom with a shaved top. “You can plant your pumpkin seedlings tomorrow.”

I stared at him. “What about the frost warning?”

“False alarm,” he said with a shrug.

“You could’ve told me,” I grumbled.

“I just did.”

“She’s just mad because Sam got his seedlings in before her,” Marylee piped up, sucking on a green bean like it was a straw.

Almost every kid on Madeline Island grows a giant pumpkin to compete in the annual Madeline Island Pumpkin Race. You start your seedlings in the spring and the pumpkins grow big and round over the summer. In the fall you hack off the top of your biggest one, scrape out the slimy guts, line it with itchy burlap, haul the hollowed-out pumpkin down to the lake, jump inside, and race it across the bay using a kayak paddle.

Last year, just as I was about to blast across the finish line, Sam sideswiped my pumpkin, breaking it into raggedy chunks.

When he threw a look over his shoulder and saw me bobbing in the water, he looked guilty.

He’d cheated, and he knew it. It’s against the rules to ram another racer’s pumpkin.

Afterward, he flat-out denied it. He said my pumpkin cratered because of all the rain that spring, that my pumpkin was too waterlogged to hold together.

The judges hadn’t seen what happened, so it was his word against mine.

That was bad enough, but then I kept losing to him all through sixth grade.

At the all-school spelling bee, I got hubris wrong and he got escarpment right. Then, at the science fair, Ms. Bagshaw was very impressed with his acid test to tell minerals apart and not so impressed with my comparison of the different respiration rates in goldfish versus humans.

“I’m gonna win the race this year,” I declared.

My mom looked up from her plate.

“Life isn’t about winning, Billie.”

I didn’t say anything. Because it is about winning, and everyone knows it. Even grown-ups know that.

That’s why they don’t cheer when you lose.

The next day Sam’s rooster woke me up. Some kids think a rooster is the same as a turkey. I wish Sam’s rooster would turn into a tom, which is a turkey, and go to freezer camp while he waits for his turn to be Thanksgiving dinner.

I wiped the sleep from my eyes. “You awake?” I asked, peering down at my sister from the top bunk.

Marylee’s eyes popped open. “I am now.”

I slid down the ladder to the floor and dug around in my closet for my favorite cutoffs. They were stuffed behind the old telescope Sam bought at the flea market last summer when he was obsessed with cosmology. I thought cosmology was the department where my mom bought her lipstick. Not even close. Cosmology is about how the universe began and where it’s going.

When Sam found out the universe is actually expanding, he wanted to see it with his own eyes, so he got the telescope. We saw cloud bands on Jupiter and rings around Saturn, but we never saw the universe expand.

Mostly we just stargazed.

We’d lie on the grass and stare up at the night sky. The lineup was always changing, depending on the season, so it was like a never-ending light show.

Now Marylee and I slid out of our pajamas, yanked on shorts and T-shirts, slithered into our flip-flops, and snuck down the hall. My mom was still asleep, lying flat on her back, the sheet stretched tight across her belly. She was imitating a giant white sand dune that got lost on its way to the desert.

A plate of freshly baked cinnamon rolls was waiting on the kitchen counter. They were covered with fat wiggly lines of frosting. Think white caterpillars, only you don’t want to lick a caterpillar.

My dad always makes us breakfast before he goes out on the lake to fish. Sometimes he bakes squash biscuits where you can’t taste the squash, or bran muffins that don’t taste like sawdust, or he makes zucchini pancakes that are bright green but still taste like regular pancakes.

My dad can make anything or fix anything or build anything. My mom says he has magic in his hands, which sounds silly, but I guess that’s the kind of thing you say when you love someone.

I carried the rolls out to Cami and her little sister, Turtles, who were already waiting on our back porch. Cami and Turtles live across the road on their apple farm. Their mom and dad also raise llamas. People buy llamas as cute yard pets, until they discover their cute yard pet will spit at you when you try and teach him tricks. And llama spit isn’t really spit. It’s vomit. They can shoot it at you from ten feet away. When people try to bring the llamas back, they find out there are no exceptions to the “no return” policy.

It can get loud over there, which is why Cami and Turtles like hanging out at our house.

Cami has hair the color of fresh-cut straw, and hazel eyes that sometimes pretend to be green like mine. She’s obsessed with learning all the words in the English language; she says there are about two hundred thousand. She told me she’s going to learn five words a day until she meets her goal.

When she said that, I did the math.

Let’s say she lives to be ninety years old. She’s twelve, like me, so that leaves seventy-eight more years made up of 365 days a year. And 78 x 365 = 28,470 days. If you multiply 28,470 days by 5 words a day, you get 142,350 words. I didn’t want Cami to give up on her dream, so I didn’t mention the fact that she’d need to learn seven words a day for the rest of her life to meet her goal.

Cami loves words, but I love numbers. Which is why I love math. Math is black-and-white. The answer is right, or it’s wrong. That’s why I’m going to be a mathematician when I grow up.

Turtles is six, with hair the color of chestnuts, like Marylee’s. Her real name is Hannah, but everyone calls her Turtles because she never goes anywhere without Hector, her pet turtle. Ever since she heard that sea turtles were becoming extinct, she’s been afraid Hector will become extinct even though he’s not a sea turtle. He’s a red-eared slider. I don’t know how Hector isn’t already extinct, since she mostly feeds him little chunks of lint-covered Heath bars and stale Oreos she keeps in her pocket.

Turtles says she’s going to fight for animal rights when she grows up. She claims there are 70 million pet dogs and 74 million pet cats in the United States alone, and they all need to be set free. I don’t think she understands that 144 million dogs and cats roaming the country looking for kibble would not be a good thing, but try telling that to Turtles.

We gobbled up our cinnamon rolls like we were in an eating contest. After we cleaned the plate with our sticky fingers, we pounded down the steps to the basement, where my pumpkin seedlings were lined up in neat rows, ready for planting. Marylee and I started the seeds a month ago, in early May, to get a jump on the growing season while there was still a threat of frost.

We worked fast to lug thirty peat pots up to the porch. Since I was already behind, I wanted to get my seedlings into the ground.

“We have a plethora of seedlings,” Cami said, her hands on her hips, “and I’m in a quandary over which ones to plant first.”

“Can’t you practice in your head?” I asked.

“What did I say to elicit such a sense of persecution.”

“School’s out, remember?” I said, but I couldn’t help smiling.

“Are you sure you got the right seeds this time?” Cami said, squatting down to inspect the seedlings.

“Don’t remind me,” I mumbled.

“Did you check the labels?”

“Stop harassing me.” That was one of her words from yesterday.

Three years ago, when I was finally old enough to

race, I planted miniature Australian Blues instead of Atlantic Giants. By the time I figured out my mistake, it was too late in the season to start new seedlings. I wish Cami would stop mentioning it. It’s not like she’s never made a mistake.

My pumpkin patch is a quarter acre. You need a lot of room to grow pumpkins, because each seedling shoots out a vine that can hit fifty feet without even trying. Before you know it, you’ve got a million vines crisscrossing under your feet like a bed of pale green snakes.

Since the ground is still frozen in February, I spent March and April getting the soil ready. Now I had ten mounds of dirt for planting. If Mother Nature was on my side, by mid-July, about seventy days since the seeds germinated in my basement, my vines would be dripping with flowers and ready for an army of bees to pollinate the buds.

Everyone has their own secret recipe for growing giant pumpkins. I happen to know Sam buries fish guts around each seedling, a kind of super-strength vitamin juice for pumpkins. His mom works at a fish processing plant and she brings the guts home in old milk cartons, which is disgusting to me but not to pumpkins.

I was sticking with my recipe.

If you want to grow a giant pumpkin, you practically need to be an agronomist. That’s a fancy word for “dirt doctor.” Turns out dirt is way more complicated than you’d think. Since we live near the lake, we have sandy soil, so I have to dump in lots of peat moss, buckets of coffee grounds to jack up the nitrogen, powdered seaweed to add copper and phosphorus, and molasses to smother everything in calcium and magnesium.

Getting the right balance is tricky. Too much nitrogen, and your pumpkins don’t grow fast enough. Too much potassium, and your pumpkin can explode, spewing seeds like shrapnel. Too little potassium, and you end up with a bunch of orange runts.

The Pumpkin War

The Pumpkin War