- Home

- Cathleen Young

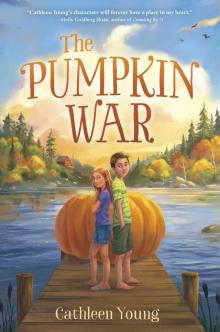

The Pumpkin War Page 3

The Pumpkin War Read online

Page 3

I hated to think of those bees flying all over the world and never finding their way back home to their queen.

Just as I dumped the sugar water into the last hive, I looked up and saw Sam running down the hill toward us. He jumped over the fence, like a runner over a hurdle.

“Check your bug traps,” he said as he ran up.

“I don’t need your gardening advice.”

“Billie,” he said. “Just do it.”

I usually checked my traps first thing each day, but today I’d started with my bees.

Without saying a word, Cami and I barreled around the side of the barn, our feet pounding the ground. We skidded to a stop at the far edge of the pumpkin patch where my traps were hanging from the poplars.

I grabbed one and peered inside.

There they were.

Cucumber beetles. Some were still alive, trying to pry their wings off the sticky lining.

I would know them anywhere, with their fat yellow bodies and the ugly black stripes running down their backs. Prison suits for bugs. I wished they were in prison and not in my pumpkin patch.

To get rid of cucumber beetles before they wipe out your entire crop, you have to inspect every single vine and every single leaf like your life depends on it. You have to peer into all the dirt cracks around each plant, where the larvae like to hide out, because each larva sac has hundreds of grubs waiting to be born, and those grubs love nothing more than munching on pumpkin roots. Once the roots are ruined, the pumpkins slowly die on the vine, waiting for food that never comes.

We ran to the barn and grabbed rubber gloves and tweezers from the tool bin.

Sam came, too.

“I don’t need your help,” I said.

“Stop being so stubborn,” Sam said calmly.

“Stop being so annoying,” I shot back.

“You could also say, ‘Sam, stop being vexatious,’ ” Cami said.

“Stop being stubborn, and I’ll stop being vexatious,” Sam said, grinning.

I considered my options. Since you can’t win a pumpkin race without a pumpkin, and Sam did cheat me out of my win last year, if he wanted to help me win this year, who was I to say no?

We spent all morning battling cucumber beetles. Armed with tweezers, we’d flick one bug at a time into a big bucket of water. My dad said it was a painless way to go to bug heaven. It didn’t look painless, but it did look quick. I felt bad about drowning a bucket of helpless beetles, but I had no choice.

While I was stabbing and grabbing cucumber beetles left and right, Sam blathered on about Einstein, his new best friend.

“Who even is Einstein?” Marylee asked.

“The most famous scientist in the world,” Sam said.

“Why’s he so famous?” Turtles asked.

“Because he figured out how matter and energy interact across the universe,” Sam said. He wasn’t even showing off. That’s how he talks.

In my entire life, I have never once asked myself “how matter and energy interact across the universe.” Why would I? I’m twelve. My brain isn’t even fully developed! That’s what Ms. Bagshaw told our whole class during the section on puberty in Science and Health. She also mentioned that going through puberty can make your feet stink. Which is why I wash my feet really, really, really well every single night.

“I keep wondering how we got here,” he said.

“Where?” Marylee said, confused.

“Here.”

“Um, you walked across the meadow…and…we live here?” she said.

“Not here,” he said. He opened his arms wide like a conductor in front of an orchestra. “Here. This world. Our universe. I can’t stop thinking about the big bang theory.”

“What bang?” Marylee said. “I didn’t hear a bang.”

“It was fourteen billion years ago, silly,” he said, ruffling Marylee’s hair as she giggled.

I didn’t tell him that I was not thinking about the big bang theory, so he took it as an invitation to keep going.

“And right after the BANG, the universe expanded like crazy and the very first atoms showed up.”

“But what made the BANG go BANG in the first place?” Marylee asked.

I was tired of his science lecture.

“Seriously?” I said, scoffing. “That’s the whole theory? There was a BIG BOOM and the entire universe just appeared?”

“Well, it was like the kickoff in football,” he said.

“If I were a scientist, I’m pretty sure I’d be able to come up with a better theory than that.”

“I’m sure you could, Billie,” he said, smiling.

* * *

The last thing we did was wash down all the vines and all the leaves with organic soap, which is supposed to kill off any beetles lucky enough to escape the tweezer massacre, but all the soap really does is get your hands super clean. We don’t use pesticides, because we don’t want to scramble a bunch of bee brains.

“When are we going to harvest the honey to sell on the Fourth?” Sam asked when we were done.

Sam was a good actor. Every year, he always got a part in the school play. Right then he was acting like everything was normal.

“We?” I said.

“We’re partners,” he said as he brushed dirt from his pants.

“We were partners,” I told him. “Now we’re just neighbors.”

“Have it your way,” Sam said, grinning. After a quick running start, he leaped over the fence, and floated through the air as if he had the hollow bones of a bird.

* * *

That night, sleep kept skittering away from me.

I looked over at my collection of first-place blue ribbons pinned to the bulletin board above my desk, lit by a slash of moonlight.

There was the one for best handwriting in kindergarten.

And the one for learning the most vocabulary words in second grade. And for memorizing the multiplication tables before everyone else in third grade.

For spelling prowess correctly at the fourth-grade spelling bee and for turning a lemon into a battery for the fifth-grade science fair.

That had actually been Sam’s idea, but he’d said I could do it since he wanted to grow bacteria in a petri dish.

I hadn’t bothered pinning up my red second-place ribbons. Second place is just the first-place loser.

From my top bunk, I could see across the meadow to Sam’s house. His window was lit up, a tiny postage stamp of light. He probably had his face wedged into some Einstein book.

My hand grazed the flashlight I kept jammed between my mattress and the side of my bed. In the old days, I would use it to send Sam messages in Morse code. We would talk like that for hours, forming words with pulses of light flying back and forth across the meadow like shooting stars.

But all the words stopped after last summer.

The next day, I woke up before the sun.

The cold morning air nipped at my skin as I yanked up my raggedy cutoffs and pulled on my favorite tie-dyed T-shirt. As soon as I checked my vines, I’d head out to the lake. I’d promised Grandma a big bucket of walleyes for the morning rush at her diner, Biscuits & Bass.

While Grandma’s famous for her buttermilk biscuits, she also makes pierogi, which are Polish dumplings, only instead of using mashed potatoes and cabbage, she stuffs them with fish and beetroot. They sell out fast to the fishermen who are her regular customers—not to mention all the city people who’d be in town the next day for July Fourth.

I tried to slip away without waking up my little sister, but I forgot about the creaky board by the door.

“Where’re you going?”

She sat up in bed, half-asleep. Her biggest fear in life was being left behind when I headed off somewhere.

She scrambled out of bed and yanke

d on her jeans. “I want to come.”

“No, you don’t.”

She looked at me. “You diggin’ for worms?”

I nodded.

She swallowed hard.

Last summer, I threw a big ol’ slimy red wiggler at her, thinking she’d giggle and jump out of the way. Only, it got stuck in her hair, and before I could pluck it out, she went crazy, screaming and clawing at her head like it was on fire, accidentally turning that red wiggler into worm sushi.

I still felt bad about it. I was just glad she didn’t have eyes in the back of her head so she couldn’t see me picking worm bits out of her hair all that afternoon.

At least worms don’t have much blood.

“You promise not to throw one at me this time?”

“Absolutely.”

I grabbed a bucket and a bottle of shampoo, and then we slipped out of the house. Before we headed to the dock, I checked the traps. Not one cucumber beetle. I went up and down each row and double-checked all the vines and all the runners. No sign of any nasty little invaders.

“Billie!”

I looked across the meadow. Sam was watering his patch.

“Your nasturtiums are ready!” he yelled. “Want me to bring them over?”

“I can get them myself!”

Marylee waited while I ran over to the glassed-in nursery plunked right between our farms. I found the nasturtiums nestled between the peonies and the marigold seedlings and grabbed two trays.

Every year, Dad gave Sam’s mom a wheel of our homemade cheddar cheese in exchange for the nasturtiums. I plant them between the pumpkin rows because bees love the nectar buried in their blossoms. They come for the nasturtiums, but they end up pollinating all my pumpkin buds so they’ll turn into actual pumpkins.

It’s like giving a kid ice cream before they do their homework, even though that never happens in the real world.

I left the seedlings in the shade for planting later. Then Marylee and I headed for the lake, running full tilt through fat tufts of purple chicory. In the summer, Mom would get all excited and dig up a big mess of chicory roots and make “poor man’s coffee,” which she used to drink when she was a teenager. She said she liked to drink it for a trip down memory lane.

I tasted it once. It was brown water pretending to be coffee. Not that I even drink coffee.

We cut through a stand of birch trees that spilled us out near the lake.

The water was as smooth as Jell-O, but everyone on Madeline Island knows you can’t trust the weather.

My dad loved to spout weather sayings. “A rainbow in the morning gives you fair warning.” “When the stars begin to huddle, the earth will soon become a puddle.” “Birds flying low, expect a rain and a blow.” He’d taught me to keep an eye on rainbows and stars and birds.

My grandma’s diner is an old ice-fishing shack bolted to the end of the floating dock that pokes into the lake. The waves make it rock gently back and forth, which is why mostly fishermen eat there. Fishermen don’t get seasick eating their runny over-easy eggs at the counter. I’d seen more than one tourist bolt from the counter and barf my grandma’s prize-winning pancakes into the lake, which made the minnows hiding under the dock crazy happy.

Now the sky to the east had a tiny hint of light sneaking up on it. When we reached the dock, I could see Grandma through the steamy window, bent over the grill cooking a mountain of hash browns. In the summer, Grandma runs her diner. In the winter, she’s an auctioneer. She went to a special school to learn to talk fast and “enunciate crisply.” So all winter, she travels around the country auctioning off cows and pigs and horses and cars and rickety antiques. Sometimes she gets lonely, but mostly she loves it.

My boat was tied up halfway down the dock. It wasn’t fancy. Just twelve feet long, made out of tinny aluminum with an old rebuilt outboard motor bolted onto the back. But it was mine.

We pulled on the ratty life jackets I kept stuffed under the seats, and headed out, skimming across smooth black water. As we zipped past the end of the dock, Grandma swiped her hand across the steamy window and waved.

I smiled and waved back.

“Hold on,” I yelled to Marylee, my hair whipping around my face. The engine whined as we picked up speed, and we sliced neatly through little rippling waves. I cut sharply back toward shore and rammed my boat up onto the sandy beach as far as I could. I jumped onto the sand, grabbed the anchor line, and tied a slipknot around a waterlogged tree trunk washed up on the beach.

“You coming?” I asked, grabbing my bucket. I dunked it into the lake and filled it with slushy water.

Marylee shook her head and hunched her shoulders higher.

Walleyes love chomping on worms. Especially big, fat red wigglers. I clomped around until I found a thick bed of old, moldy leaves in the middle of a grove of sugar maples. I dropped to my knees and cleared away the wet leaves and the slimy slugs until I could see the dirt.

“Wake up, little guys,” I whispered, squirting a long stream of shampoo into the bucket of water. I swished the water with my hand, stirring up a big mound of bubbles, before I dumped the soapy water over the dirt.

My dad says it used to be a lot harder to dig up worm bait, but now the whole state of Wisconsin is stuffed with angleworms and red wigglers. The newspaper calls it an “alien invasion” because the worms are hogging the good dirt and choking off the plants in the woods. My dad blames the beer-drinking, trash-spewing weekend fishermen who buy night crawlers from vending machines in the city, then dump the leftovers into the woods after a day on the lake catching salmon they don’t even eat.

I smiled as dozens of squiggly red wigglers and angry angleworms shot out of the ground like fleshy rockets. Grandma taught me this magic trick. She said worms hate baths, just like kids do, but the truth is, they don’t want to suffocate to death in soapy water. So they wriggle to safety, not knowing that they’re actually headed straight for the sharp end of a bait hook.

I scooped up dozens of slimy worms and tossed them into the bucket, along with a handful of dirt. Worms feel naked without dirt to hide in. Besides, the sight of a bunch of naked worms might make Marylee start crying, because she knew what was waiting for them out on the lake. One minute they were daydreaming in their cozy dirt beds, and the next minute they were dinner in the belly of a fish.

I jogged back, lugging my bait, and plopped the bucket into the boat. The worms were trying to escape by crawling up the sides, but since worms don’t have hands, that wasn’t going very well.

“Billie.” Marylee pointed at the worms, frowning. “They’re scared.”

“They have brains the size of a flea!” I said. “They don’t even know what’s happening!”

“Worms have ears, you know!” she said. “They can hear you!”

“Actually, red wigglers don’t have ears,” I said. “Or eyes. Or teeth. Or bones.”

“They still know you’re mean.”

I pushed us off and hopped into the boat without getting my tennis shoes wet.

As the light from the east seeped across the sky, Marylee and I took off across the water. In the distance, I saw my secret fishing hole.

And I saw Sam.

In his boat.

Ready to fish.

I let the throttle out, and we skimmed across the water.

“What’re you doing here?” I yelled as we raced up.

“What’s it look like I’m doing?” he said. “Hi, Marylee.”

“Hi, Sam,” she said, smiling at him.

“This is my fishing hole,” I snapped.

“It’s a free world,” he said as he threw out his line. He got a bite on his hook right away. I watched as he wrangled the big, fat brown trout twisting and twirling at the end of his line.

“Sam,” Marylee said. “Did you figure it out? The stumper?”

/>

“Not yet,” he said.

I gave her a look. “Since when are you interested in Albert Einstein?”

“It’s a free world,” she said with a giggle. Right in front of her, I threaded a fat red wiggler onto my hook. She glared at me and then looked away.

“But I did find out what happened to him after he died,” Sam said.

“Stop talking,” I said as we drifted closer to Sam. “You’re going to scare away the fish.”

“After he died?” Marylee whispered loudly.

“Someone stole his brain. Sawed off the top of his skull and just scooped it out.”

“Why?!” Marylee said.

“To figure out what made him so smart. They sliced his brain up and looked at it under a microscope.”

“What did they see?” Marylee asked, covering her mouth in horror.

“You want to hear something weird?” Sam turned toward me.

“No.”

“I want to hear,” Marylee said.

I shot her another look.

“You’re not the boss of me,” she said, cocking her head with her hand on her hip.

Sam grinned at Marylee. “His brain was smaller than normal.”

“Really?” Marylee said.

“Yeah. Except it had more glial cells.”

“What’s a—”

“They protect the neurons in your brain.” I said. I only knew that because we studied the nervous system last year.

“I thought you weren’t listening,” he said.

I clamped my mouth shut.

“I hope no one ever tries to steal my brain.” Marylee touched her head.

While he went on and on about how Einstein loved to ride his bike and sail his boat and play his violin, I stuck another wiggly worm onto my hook and tried to focus on fishing.

The Pumpkin War

The Pumpkin War