- Home

- Cathleen Young

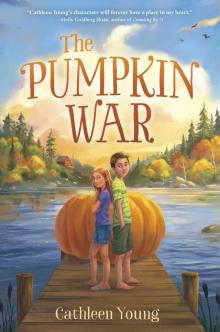

The Pumpkin War Page 7

The Pumpkin War Read online

Page 7

I set the coffee mug on the ground nearby, plopped myself down on an old milking bucket, and waited. When he peeked out of his sleeping bag and saw me, he smiled and rubbed his face.

“Well, isn’t this the most lovely way to start the day,” he said as he rose onto his elbow. He looked at the coffee. “Is that for me? Don’t be teasing an old man.”

He picked up the cup and took a long, slow sip.

“Why is my dad so mad at you?” I asked.

He took another slow sip before he answered.

“Who doesn’t love a girl who gets right to the heart of the matter?”

“You didn’t answer the question.”

“I imagine he’ll be telling you when he’s ready.”

“Well, I’m twelve, and he hasn’t told me yet.”

Grandpa climbed out of his sleeping bag. He was wearing jeans and a wrinkled flannel shirt. He stretched and looked around our farm.

“Just look at all the tree fruit that’s come out to say hello,” Grandpa said. “You’ve got walnuts waving and wild plums falling and meadow rue flowers winking at us like eye candy.”

“How do you know so much about nature?” I asked.

“I can’t even count the times I have walked from one end of Ireland to the other,” Grandpa said.

“Don’t they have cars in Ireland?”

“They have cars,” Grandpa said. “For those who can afford them.”

I asked my new grandpa what he did in Ireland.

“I’m a seanchai,” he said.

“A shawn-who?”

“A seanchai. That’s Irish for ‘storyteller.’ ”

“That’s your job? Telling stories? Is that a real job? Where you get paid?”

“Thousands of years ago, Ireland was wild and lawless. A bunch of fierce clans ruled the land. Each clan had a chief, and each chief had a seanchai who kept track of the clan history with poems and songs that were passed down from generation to generation.”

“Was your father a seanchai?”

“He was. And his father before him. And his father before that. And on and on back in time for centuries and centuries. I followed in their footsteps.”

“Why didn’t my dad follow in your footsteps?”

He didn’t answer right away.

“I am a storyteller,” he finally said. “And just like a cow needs to be milked, I need to tell stories. About my people and my country. It’s in my blood and it’s in my bones. But it’s not an easy life, walking from town to town, sometimes being paid with potatoes and a pint, sometimes being paid with a smile, which is lovely, don’t get me wrong, but it doesn’t soothe the hunger that comes to live in your belly.”

I tried to think of all the times I’d been hungry in my life. Who was I kidding? Wanting two desserts doesn’t count as being hungry.

“Your father wanted better for himself. There was nothing for him in Ireland.”

“But you were there.”

Grandpa sighed. “True enough. But I was a father in name only. Not in deed.”

“What do you mean?”

“I wasn’t a good father.”

No wonder my dad never wanted to talk about his life before he came to America.

After Grandpa finished his coffee, he went to clean up in the outdoor shower beside the barn.

Just then, Ricky’s truck turned into our driveway. By the time I jogged down the hill, he was waiting for me.

“It hurts me to say this, but I’ve used every trick I know, and I just don’t know what else to do. I hate to see your daddy throw more good money after bad when I can’t help you.”

As I shifted from one foot to the other, Ricky gave me a rundown of his “abatement history.” He’d used cream of tartar, cinnamon, garlic, chili pepper, paprika, and dried peppermint to get rid of the field ants. None of it worked. He even spread petroleum jelly around the base of the tree, but the ants thought it was a Fun Zone at an amusement park and kept on coming.

“And those pigeons!” Ricky said. “That was a first!”

A posse of pigeons had shown up after the ants, with their special calling card: white poop. It’s white because birds don’t pee. Well, they pee, but their pee mixes with their poop and somehow turns it into white paste. Ricky told me it was from uric acid and that “back in the old days,” people used to turn this stinky paste into gunpowder. The pigeons had a lot of fun spray-painting my tree house with their almost-gunpowder.

Hordes of chiggers and fleas and flies and lice had shown up with the pigeons. Ricky had hung fly traps and washed everything down with tea tree oil. None of it worked.

“This is my first real defeat in the animal kingdom, and I’ll be honest with you. I’m taking it kinda hard.”

“Well, thanks for trying, Ricky.” I tried to be polite.

After he left, I headed over to my pumpkin patch, kicking at the dirt with the toe of my tennis shoe as I went.

I suddenly noticed the hum of buzzing bees.

My bees.

Flying right past my pumpkin patch. It was like watching a bee freeway with one exit ramp. And that exit ramp led straight up the hill to Sam’s pumpkin patch.

This can’t be happening, I thought, just as Grandpa rounded the corner of the barn, dressed and showered.

He took one look at my face and said, “What’s wrong?”

“My bees aren’t doing what they’re supposed to be doing.”

Grandpa looked around the garden, tracking the bees with his bright green eyes. He waded into my patch, carefully stepping over clumps of spiky red-and-yellow marigolds and raggedy clusters of peppers. I followed right behind him.

“What are you looking for?” I asked.

“I’ll know when I find it.”

I inched along slowly so I didn’t crush any of the vines underfoot.

Grandpa stopped by the long, wiggly line of nasturtiums, which hadn’t flowered yet. He kneeled down, pinched off a leaf, and peered at it.

“Here’s your problem,” he said, lifting up the leaf.

“What?” I said, confused.

“You planted chrysanthemums. Bees hate chrysanthemums.”

“I planted nasturtiums,” I said. “Bees love nasturtiums.”

“If you planted nasturtiums, your bees wouldn’t be feasting up the hill at your friend’s patch.”

“He’s not my friend,” I snapped as I took a closer look at the leaf Grandpa was holding. It was serrated, like a knife, only not with hard edges. More like ripples. Nasturtium leaves were shaped like lily pads.

Grandpa was right.

Those were chrysanthemums.

I whipped around and looked up the hill.

Cami and Sam were watering his pumpkins.

“REALLY, SAM?” I yelled.

Sam looked across the meadow. I reached down and started ripping the chrysanthemums out of the ground, flinging them through the air until it was raining dirt. When I looked up, Sam was running down the hill, Cami following.

At the bottom, he jumped over the fence and jogged toward me.

“What’s wrong?”

“You were supposed to give me nasturtiums!”

“Billie—”

“BEES HATE CHRYSANTHEMUMS!”

“Billie, will you listen—”

“Shut up! Just SHUT UP! This is all your fault! You gave me the wrong flowers!”

“No! For once YOU shut up! I didn’t give you the wrong flowers! You took the wrong ones!”

I realized he was right.

Which made me even madder.

“GO HOME,” I yelled, right in his face. “I DON’T WANT YOU HERE!”

“Billie!” Cami snapped. “It’s not his fault!”

Sam stared at me. He frowned, cocking his head to

one side. Then he sucked in a deep breath and slowly let it out.

“You know what?” he yelled. “I give up. That’s what you want, isn’t it?”

“Yes! That’s exactly what I want! Thanks for finally getting it!”

“Billie!” Cami said. “Stop being so mean!”

“Be quiet!” I glared at her.

“YOU be quiet!” she yelled, putting her hands on her hips.

“I thought I could get through to you, but I can’t!” Sam said. “You’re too stubborn! So guess what? I’m done trying to be your friend. It’s like you said. We’re just neighbors. And not the friendly kind! So you win!”

“No! You won! Remember? By cheating!”

He started to walk away, then turned back.

“By the way,” he said, “I used your magic recipe on my pumpkins. Thanks for that.”

“That’s stealing!” I yelled.

“Really? I thought it was sharing. And sharing is caring. Didn’t you learn that in kindergarten?”

He turned away and headed across the meadow.

“Everybody hates you!” I yelled at his retreating back.

“Everybody hasn’t met me yet, Billie, so you’re wrong again!”

“BILLIE!”

My head whipped around at the sound of my dad’s voice. “Who are you to be talking to Sam like that?” He stood in the driveway, a bucket of trout in his hand. “That’s not how we talk to our neighbors.”

A hot bubble of anger climbed up my throat and shot out of my mouth. “Who are YOU to tell ME how to talk to people? YOUR OWN DAD CAME ALL THE WAY FROM IRELAND, AND YOU WON’T EVEN LOOK AT HIM.”

“That’s enough, young lady!”

“Billie,” Grandpa said softly.

But I couldn’t stop.

“He’s been sleeping outside, waiting for you to look his way, and you tell me I’m not acting right? Well, you know what? WHY DON’T YOU GO LOOK IN THE MIRROR?”

“BILLIE! THAT’S ENOUGH!” My dad’s face was flushed bright red. I didn’t care.

I ran to the porch. As I jerked open the screen door, I saw Sam at the top of the hill. He sank to his knees, fell forward into the grass, and rolled over to stare up at the sky.

Why was everyone on Sam’s side?

My sister. My dad. My grandma. Cami. Turtles.

Everyone.

I went into the house and slammed the door as hard as I could.

* * *

That night, my dad made cauliflower mac ’n’ cheese, one of my favorites, but I refused to eat. He pretended not to notice, because he was mad, too.

I slammed out of the kitchen as soon as the table was cleared and went to my patch to pollinate my blossoms by hand.

One by one, as the sun sank down below the horizon, I peeled back the leaves on the boy blossoms, carefully pinched off the stamen, plunged it into the center of the girl flower, and rubbed it on the stigma, which looked like a tiny bowl of spaghetti.

I did what the bees were supposed to do. Only, instead of tracking pollen from flower to flower with hairy, spindly legs and clawed feet like a bee, I used my hands.

My sister was already asleep by the time I climbed into bed. My knees were rubbed raw from crawling around in the dirt all night.

As I nestled into my cool sheets and hiked my quilt up to my neck, I glanced through the window and across the meadow.

Sam’s light was still on.

My eyes drifted up to the night sky and the Milky Way.

Ms. Bagshaw said there are over two hundred billion stars in our galaxy alone. She also said there’s a black hole right smack in the middle of those stars.

I wished Sam would disappear into it.

Ever since our big fight two weeks ago, Dad and I still weren’t talking. We were trapped in a fog stuffed with all the angry words we’d said.

Dad and my new grandpa were not doing much better. Grandpa kept trying to talk to Dad, and Dad just kept pushing him away. My dad was stubborn.

On top of that, it was August.

In August, it seems like all I do is work.

Starting with fishing.

The lake water is warmer in August. Well, to a fish, it’s warmer. To a kid, it’s still freezing cold. Fish don’t like warm water, so Dad has to throw out long nets and troll along the bottom, where the water’s cooler.

And even though Dad and I were mad at each other, I still had to help him.

I had to bait the hooks with dead smelt that smelled like rotten eggs and crank up the lines when we got lucky and snagged some wild trout. When you snag a razor-sharp hook through the mouth of a wild trout, he fights like crazy the whole way up.

After fishing, I helped Dad get his blue cheese ready to sell to all the big-city chefs who came for the Harvest Festival in October. My job was to blend in the mold that makes those wiggly blue veins.

I try not to think about people eating mold. It makes me gag. On the other hand, mold is also used to make penicillin, which saved Sam’s life once when he got bronchitis so bad it turned into pneumonia and every time he took a breath, it sounded like two pieces of sandpaper rubbing together.

I guess there’s good and bad in most things.

And every day there were my pumpkins.

My orange babies were packing on the pounds, sometimes adding thirty or forty pounds a day!

I had to get rid of all the pumpkin wannabes and make room for my best growers, since each main vine can only feed one giant pumpkin. If you want to top a thousand pounds, every single nutrient needs to go to that one pumpkin.

The first thing I did was pinch off all the pumpkins from the secondary vines. Now those vines would send all their food to the main line.

I’d spent weeks walking around with my measuring tape draped around my neck, jotting down measurements to fill in the growing calendar taped to the kitchen door. I’d measure the circumference and plug that number into the weight table. I had some pumpkins taping out at a hundred inches around, which meant they were around three hundred pounds. I had some pumpkins pushing one hundred forty inches around, which meant they were over six hundred pounds.

So I was a pumpkin nanny.

Just like babies, my pumpkins had to be bottle-fed, only I did it with a big rubber hose. While they sucked up hundreds and hundreds of gallons of water every day, I had to keep them resting on a mound of dry sand and covered with sunshades. The fact that we were having a summer with record rainfall also helped my pumpkins pile on the pounds.

I saved the worst for last.

The llamas.

I don’t like llamas.

Besides all the smelly spit, llamas are a ton of work.

But Cami and I had a deal. She helps me with my pumpkins and I help her with her llamas. There’s no way for me to wriggle out of it.

So every August, I help shear the llamas so Turtles and Marylee can spin the hair into yarn over the winter.

The word shear is very misleading. It sounds like something a made-up character in a fairy tale would do.

He sheared past the princess before he realized the danger he was in.

It was nothing like that.

Shearing a llama means wrangling a pair of electric clippers longer than my forearm and hoping the six-foot-tall, three-hundred-pound beast pawing the ground next to you will think that getting all his hair shaved off is a good idea.

And today was shearing day.

As soon as the sun was up, I headed down the meadow and across the road. I found Cami waiting for me outside the barn, dressed in muddy overalls. She was leaning on the paddock fence, her elbows planted on smooth rails that looked like the old gray bones of a skinny giant.

“Ready?” I asked.

“First we gotta catch ’em,” she said quietly.

Even though Cami

and I made up at the powwow, we were still a little distant with each other. I wasn’t going to change her mind, and she wasn’t going to change mine, so we just avoided talking about it.

I looked at the pack of dirty, hairy llamas huddled in the far corner, waiting for us to make the first move as they stared us down. At least, I think they were staring at us. It was hard to tell because their beady little llama eyes were hidden under halos of stringy white hair. They could be Einstein’s relatives, except they had four legs instead of two, and brains so small they could fit in a teacup.

Cami grabbed a long wooden pole with a hook at the end that reminded me of something you’d use at the circus to yank a clown off the stage. She handed me a grimy halter. “Remember. Divide and conquer.”

We hopped over the fence. Cami went to the left, and I went to the right. The biggest llama let out an earsplitting bray, and they all started to hum to each other.

That was llama talk for “uh-oh.”

At least they weren’t spitting at us.

When we got too close, the whole pack stampeded. I froze and squeezed my eyes shut tight as eighty feet pounded past.

Well, they didn’t really pound. More like they padded past. Because llamas don’t have hooves. They have toes. Two fat, leathery toes, just like a camel.

After a bunch of near misses, Cami got the hook around Jimmy.

Jimmy squealed like an angry pig and spit at me as I shimmied the halter over his soft muzzle and slipped it around his neck. After Jimmy, Cami quickly hooked Paco. Only because he stood still and let her. Probably because he was the littlest one in the pack. He knew his odds weren’t good, so he gave up without a fight.

We led them into the barn, and I tied Jimmy up using a slipknot. If he went crazy and kushed, I didn’t want him to strangle himself.

Kush is llama talk for “lie down.”

Even though llamas have four legs, they only have two knees. So when they kush, they pop down on their front knees, then tilt back like a wobbly rocking horse and collapse to the ground.

You don’t want to get tangled up with a llama when he kushes.

The Pumpkin War

The Pumpkin War